When I reflect on the title of this post, a statement made by Chinua Achebe in an interview with The Parish Review in 1994, I am struck dumb with amazement at how precise and compelling a case it makes! For it clearly depicts the situation of Africa, of Ghana, my own situation, and that of my motherland, Buluk (Builsa land). The truth of it is frightening! Here is an excerpt from the interview:

“Then I grew older and began to read about adventures in which I didn’t know that I was supposed to be on the side of those savages who were encountered by the good white man. I instinctively took sides with the white people. They were fine! They were excellent. They were intelligent. The others were not . . . they were stupid and ugly.

That was the way I was introduced to the danger of not having your own stories. There is that great proverb—that until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter. That did not come to me until much later. Once I realized that I had to be a writer. I had to be that historian. It’s not one man’s job. It’s not one person’s job. But it is something we have to do so that the story of the hunt will also reflect the agony, the travail—the bravery, even, of the lions.”

Although this statement speaks volumes about the African story, I shall restrict my comments and concerns to the situation of the Builsa people for as I always said, ‘if a stone is falling from the skies, everyone covers their own head!’ The African story has been written largely by the Western world and their media and we all know that it is not a good story by any standard. Within the African continent and specifically the Ghanaian situation, the nation’s story is mostly written by the southern media. And again, we see that there’s not much good in it about northern Ghana let alone about minority groups like the Builsa.

This situation is a source of frustration and annoyance to many people of northern and Builsa origin who are embarrassed and harassed by these biased and stereotypical stories being churned out about their history and homeland. Every time I reflect on this situation and the seeming absence of a concerted effort to correct the wrong stories and impressions being created about northern Ghana and the Builsa in particular, I ask the question, where are the Builsa stories and who is writing them? And by stories, I do not only mean media stories! I also mean, folktales, poetry, proverbs/wise sayings, cultural and traditional songs/hymns and expressions written in English.

|

| The title says "The Reason Why the Chameleon has a broken head!" |

Since I learned to read in Class 5 at Balansa primary school, I have been fascinated by stories. I have read many stories but I never came across a Builsa tale written in English. I had learned to read Buli from the Primary school and was familiar with the Buli literacy books which included very interesting stories, proverbs, and narratives. But they were written in Buli. I started to think that Builsa stories were not good enough to be told in English. In fact, we used to transliterate Buli expressions into English and laugh loudly, supposing that such expressions could not exist in English! That is how I grew up and I know that I am not unique in this experience.

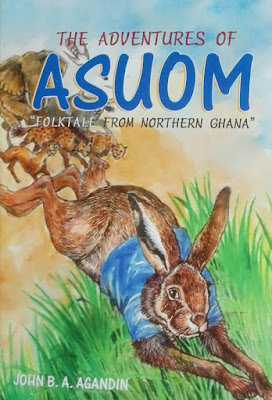

As a teacher, I taught English in Junior High School. In all, I have taught in three J.H.Ss. in Sandema. Several times, I asked my students to tell stories; hoping to hear a local story but it never happened. I could not understand why. When I ask for local stories, they tell them in Buli but not in English. None of the students could tell a story in English about Asuom, Apiuk, Akalaasing, or any of the other heroes in Bulsa tales. Beyond storytelling, I observed that when I ask a student to make a simple sentence, I often hear something like: “Kofi is a boy” or “Ama is going to school”.

I once asked students to describe their best friend and everyone started with something like ‘The name of my best friend is Kofi, Ama, Aku, Mensah, Kojo, etc’. When I asked them what about Adjuik, Amoak, Abuuk, Ayomah, Akansiing, Awogtalie, Atangbain, and co, everyone burst out laughing “Ah master paa, how can our friends be called by such names”. It was at this point that I realized the danger of not having your own stories. Yes, I know we do have our own stories, but they are not stored in a form that is available and useful to children in this twenty-first century.

The textbooks used in our schools are dominated by Akan names and the rest is filled with typical Islamic names like Alhassan and Amina which are assumed to represent names from northern Ghana. The culture of storytelling during moonlit nights may be dying out slowly especially with the expansion of electricity, television and radio sets into rural areas. All these mean that there’s a good chance many children in primary schools and below, and those yet unborn may not have an opportunity to listen to a Builsa folktale unless they are reading it in school (which is also unlikely since we do not have many Builsa folktales in print). Even the stories written in Buli are now out of print.

|

| The Hare is a popular hero in Builsa folktales. |

The danger of not having your own stories or of not having them in a form that can be preserved, transmitted, and appreciated by others outside your own small linguistic group is all too clear to us. In the absence of any authentic Builsa tales, other tales will be substituted for us. These tales will not tell our story in full and will leave us unsatisfied with their content. We may even end up not appreciating our own stories anymore. Our children will not know their own stories and may consider them as ‘primitive’ substandard’ or not important.

There is a real need for Builsa educationists, Political and Traditional leaders, academicians, and other professionals to pay attention to the development of our language and culture of which storytelling is a crucial component. Kasem is studied in colleges of education in Ghana, but Buli is not, and yet the Builsa population outnumbers the Kasena in Ghana. I do not think that the Kasem language was written by an Akan or an Ewe. Nobody can write our language for us, we have to do it ourselves. If we allow other people to write our story for us, we cannot complain about the way the story will be told or written. Or worse still, if we do not write our own stories, they will be swept under the carpet or thrown onto the refuse dump and discarded into nonexistence.

The author is a young Builsa man with a keen interest in culture and literary works. Visit my blog, Village Boy Impressions, for a peek!

You have said it all big bro!!!

ReplyDeleteAll hope is not lost, a lot can and will be done... I have great interest in any move in line with this.

I'm happy to hear you say so Mr. 'Unknown'. All of us can contribute by writing, reading, or telling our stories our-selves. We can buy Builsa stories or even sponsor others to write them. The possibilities are endless and I hope you can find an appropriate way to put your great interest into action. Best.

Delete